Whatever else it may be, Peru’s economy is essentially extractivist. Which is to say, profits are generated through the extraction of a range of natural resources, which normally undergo minimal processing, before being exported to foreign markets. Travel by road from Lima to Pucallpa, the largest city in the Amazonian region of Ucayali, and you will pass through many distinctive landscapes of extraction, perhaps most memorably the dystopian, contamination-stricken La Oroya, at the epicentre of Peru’s mining industry.

Descending from the Andes into the Amazonian lowlands, another landscape comes to dominate: as far as the eye can see, rows upon rows of a single crop: elaeis guineesis, better known as oil palm. In what follows, I look back on five of the key lessons I learnt about the expansion of oil palm in Ucayali, during the seven months I coordinated Alianza Arkana’s ecosocial justice program.

1. Palm oil production is expanding – fast

Palm oil is an edible oil native to West Africa, where it is a revered crop and is still produced using traditional methods. During the 20th century, the first industrial oil palm plantations were established in Southeast Asia; this plantation form of production has since expanded to Africa and Latin America. Oil palm was first cultivated in Peru during the 1960s, in the province of Tocache. In Ucayali, production began on a relatively small-scale in the early 1990s with assistance from the United Nations Development Program, which promoted oil palm as an alternative crop to coca.

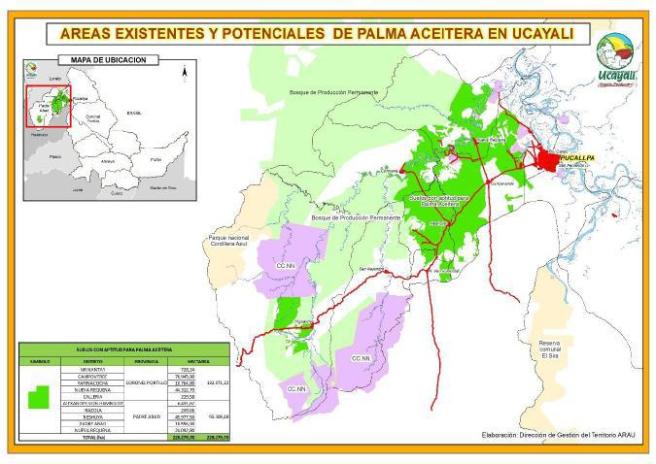

However, production has grown much more rapidly since 2008, expanding at a rate of 15,000 hectares every four years; by February 2016, a total of 35,000 hectares was under cultivation, with ten palm oil mills in operation. This accounts for around 30% of national production. Plans are afoot to expand the area under cultivation across Ucayali up to 228,000 hectares over the coming decade. With a document published by the Regional Government of Ucayali in conjunction with the private sector citing the need to meet demand both nationally (Peru imports around 70% the vegetable oils which it consumes and has also passed into law a requirement that 5% of diesel come from biodiesel), as well as internationally (big consumers such as the European Union are being joined by rapidly emerging markets in Asia, particularly those of China and India), all indications signal that the expansion of oil palm across the Peruvian Amazon is likely to continue and intensify.

2. The way in which palm oil is produced in Ucayali is changing

Whereas previously, production was led by associations of small and medium-scale producers, in recent years, this has started to change, as foreign investors look to expand their agribusiness ventures into the Peruvian Amazon. The most notable case in Ucayali is the installation of two large-scale plantations, operated by Plantaciones de Pucallpa SAC and Plantaciones de Ucayali. Both companies belong to a larger group of at least 25 companies operating in Peru, directed by businessman Dennis Melka, who previously developed plantations in Malaysia.

Melka’s Peruvian plantations have been mired in controversy and conflict, with evidence of irregularities in the way lands have been acquired and subsequently managed, the illegal destruction of primary forests and human rights violations, most notably of the Shipibo community of Santa Clara de Uchunya. Santa Clara de Uchunya have responded to this land grab within their ancestral territory by denouncing the activities of Plantaciones de Pucallpa to the Peruvian authorities and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, an industry body which certifies ‘sustainable’ palm oil.

The increasing penetration of transnational capital into agribusiness plantations in the Peruvian Amazon ‘has radically changed the situation’, in the words of sociologist Juan Luis Dammert Bello, not only in terms of the scale of projects, but also with regards the kinds of relations these companies establish with both local communities and the environment.

3. Oil palm monocultures are a bad fit with indigenous livelihoods

Many indigenous peoples have, over time, developed a sophisticated understanding of rainforest ecology and this is reflected by the varied livelihood strategies they employ to live well in the forest. Shipibo communities rely upon their traditional forests for a wide range of goods: fresh water for drinking, cooking and bathing with; hunting and fishing grounds; edible fruits and nuts for gathering; construction materials; medicinal plants and natural materials for handicrafts which can be sold to generate a cash income.

Add to this the fact that communities also require their territory in order to practice swidden agriculture, and you start to gain a sense of all that is lost when a community’s forests are cleared to make way for oil palm monocultures. As Rodit, a woman from Santa Clara de Uchunya, puts it, oil palm plantations are ‘deserts’ in the eyes of the local community.

Whilst the Regional Government of Ucayali should be lauded for sustaining that a key principle for investment in oil palm in the region is that it shouldn’t compromise food security, this must be ensured in practice, along with the recognition that indigenous livelihoods do not necessarily – and nor should they have to – conform to those of smallholder agriculturists.

4. Oil palm is expanding within the context of legal loopholes and lack of regulation

During recent years, oil palm companies, such as Grupo Palmas and the Melka Group companies, have taken advantage of certain loopholes within Peruvian legislation to facilitate the conversion of forests to monoculture plantations. Although forests are granted strict protection under Peruvian legislation, an important investigation published by the Environmental Investigation Agency in 2015 revealed that the Peruvian government’s current procedure for the classification of lands has allowed for extensive tracts of forest to be wrongly categorised as lands best-suited to agricultural production and subsequently destroyed.

Such ‘best land use capacity’ studies are based upon soil and climatic characteristics, overlooking the actual presence of standing trees, which runs counter to other provisions and protections within Peruvian law. As of 2015, more than 20 million hectares of rainforests lacked any official classification whatsoever, leaving these forests open to the kinds of predation witnessed in Ucayali, where more than 11,000 hectares of mostly primary forests have been cleared since 2011.

Furthermore, even when agencies within the Peruvian government have acted against the illegal activities of oil palm companies, regional and local authorities have proven ineffective or even resistant to upholding these measures. For example, in September 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture ordered Plantaciones de Pucallpa SAC to suspend its operations, pending further investigation. In May 2016, I was present when an official commission, led by the Environmental Prosecutor of Ucayali, went to investigate the plantation in question. The Ministry representative found that the company was continuing its activities, some eight months after the suspension order was issued. Furthermore, the Regional Department of Agriculture had continued to issue land titles over the lands adjacent to the plantation to outsiders, despite the community-members of Santa Clara de Uchunya denouncing practices of land-trafficking, leading to allegations of corruption.

This episode, along with others such as the large-scale deforestation caused in Tamshiyacu, Loreto, by another Melka company, Cacao del Perú Norte, demonstrate that at present, the Peruvian government lacks both the capacity and the political will to effectively regulate this quickly-expanding industry.

5. The expansion of oil palm is intimately linked to and mutually reinforces other threats to indigenous territories

Until now, the expansion of oil palm plantations in Ucayali has had a limited – albeit serious – impact upon indigenous communities. However, as the examples above show, oil palm expansion is closely linked to a series of other threats to indigenous territories, which would be exacerbated by its expansion. These include the lack of recognition of indigenous peoples’ land rights over their traditional lands, in contravention of Peruvian and international law, which leaves whole communities vulnerable to practices such as land-trafficking, whereby migrants move into and clear community forests in order to apply for land titles. Once these are obtained, they are subsequently sold on to companies, which are able to acquire huge extensions of land in this way. Added to this is the ongoing scandal of illegal logging, which is more prevalent in Ucayali than any other region in the Peruvian Amazon.

There are also significant infrastructural megaprojects planned for the Ucayali region, such as the dredging and industrialisation of the Ucayali river as part of the Hidrovías Amazonas project and road-construction, to link Pucallpa with Cruzeiro do Sul in Brazil. These projects have been met with concern by indigenous and civil society groups and experts, due to their projected socio-environmental impacts. Such projects, their supporters claim, will attract additional foreign investment and boost exports to overseas markets and it is undeniable that such infrastructure will only enhance Peru’s ‘business-friendly’ image. As with past extractive cycles in the Peruvian Amazon, the global context is ever-present, whether in terms of our increasingly global junk food addiction, which is driving demand upward, or the offshore tax-havens, often British Overseas Territories such as the Cayman Islands, which make it so difficult to follow the money and powerful interests behind companies such as those which make up the Melka Group.

Oil palm expansion is just one of many challenges faced by indigenous peoples such as the Shipibo in the early 21st century. What is certain is that the indigenous movement and their allies in Ucayali need to be vigilant, confident and critical in dealing with the foreign investors who are increasingly turning to the Peruvian Amazon, as lands are exhausted in key palm oil-producing countries such as Malaysia. As communities are approached by and interact with companies, it will be important for them to draw upon the often bitter lessons of communities elsewhere, such as in Southeast Asia, whose lives have already been transformed by oil palm.

Yet in spite of the challenges outlined above, oil palm-affected communities such as Santa Clara de Uchunya are finding effective ways to resist. The community’s efforts have led the Peruvian authorities to investigate Plantaciones de Pucallpa’s activities, for which they were sanctioned in early August. Following a formal complaint made by the community, the RSPO issued the company with a ‘stop-work order’ in April. A video which the community made with myself and several other volunteers has been publicly screened across Peru, in dozens of meetings with government agencies and other institutions across Northern Europe and the United States, to raise awareness of the situation. Santa Clara de Uchunya’s fight proves that when the community is unified, stands firm and enacts a series of parallel strategies, it can start to regain lost ground.

This article was originally posted on Alianza Arkana’s blog.